Introduction

The Tiger Global–Flipkart case is not just another tax dispute. It is a story about how foreign investments came into India, how exits were structured, and how India’s tax laws have evolved to deal with complex cross-border arrangements. The Supreme Court’s ruling in the Tiger Global–Flipkart indirect transfer case represents a watershed moment in India’s international tax jurisprudence.

At its core, the case answers a long-standing and highly contentious question:

Can India deny treaty benefits and apply GAAR (General Anti-Avoidance Rules) to complex offshore structures even when the investment traces its origin to a period prior to April 1, 2017?

The Court’s answer is nuanced but firm yes, where the structure is an impermissible tax-avoidance arrangement rather than a genuine investment.

The importance of this ruling extends beyond the Flipkart transaction. It impacts:

- Global private equity and venture capital funds investing in India through intermediary jurisdictions.

- Legacy Mauritius and Singapore holding structures are still present on the cap tables.

- Cross-border Mergers and Acquisitions exit involving Indian asset value.

- The scope of GAAR as an overriding anti-abuse mechanism

In essence, the judgment marks India’s transition from a form-driven treaty interpretation regime to a substance, intent, and purpose-driven tax enforcement framework.

Parties and transaction structure

The Flipkart exit

- Flipkart Pvt Ltd was an Indian company holding valuable Indian business assets.

- The immediate holding company was incorporated in Singapore.

- Shares of the Singapore company were held by a Mauritius entity.

- The Mauritius entity was ultimately controlled by Tiger Global, a US-based private equity investor.

When shares of the Singapore company were transferred, substantial capital gains arose. The legal question was whether these gains were:

- Taxable only in Mauritius under the India–Mauritius Tax Treaty, or

- Taxable in India as an indirect transfer of Indian assets under domestic law.

Why the Tax Authorities Viewed This as an Indirect Transfer

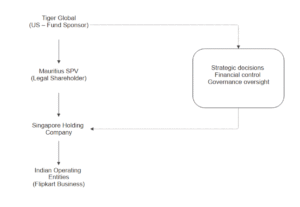

Ownership and Control Flow in the Tiger Global Structure

Legal ownership chain:

- Tiger Global (US fund sponsor)

- Mauritius special purpose vehicle (legal shareholder)

- Singapore holding company

- Indian operating entities

Key point:

This is the formal shareholding structure relied upon to claim treaty protection under the India–Mauritius DTAA.

Effective control indicators identified:

- Strategic and financial decisions taken outside Mauritius

- Limited independent authority exercised by Mauritius directors

- Absence of autonomous risk assumption at the Mauritius level.

The Court concluded that GAAR was triggered not by offshore incorporation, but by the divergence between legal ownership and the commercial decision-making.

Legal framework: Evolution Before and After 2017

To appreciate the Court’s reasoning, it is essential to understand how India’s legal framework on indirect transfers and treaty abuse evolved over time.

a) Indirect transfer provisions – Section 9(1)(i)

Following the Vodafone controversy, through the Finance Act, 2012, the Indian legislature amended Section 9(1)(i) of the Income-tax Act to clarify that capital gains arising from the transfer of shares of a foreign company would be deemed to accrue in India if such shares derive substantial value from assets located in India. This amendment firmly embedded the concept of indirect transfer taxation into domestic law.

b) GAAR (General Anti-Avoidance Rules) Chapter X-A

GAAR was introduced to deal with aggressive tax planning. Under GAAR, tax authorities can deny tax benefits if:

- The main purpose of an arrangement is to obtain a tax benefit, and

- It lacks commercial substance, results in misuse or abuse of tax provisions, or is carried out in a non-arm’s-length manner.

GAAR became effective from 1 April 2017. GAAR operates as an overriding provision and can deny treaty benefits where abuse is established.

c) Treaty amendments – India–Mauritius Protocol, 2016

The 2016 Protocol amended the India–Mauritius Tax Treaty by withdrawing the long-standing capital gains exemption for shares acquired on or after April 1, 2017. While grandfathering protection was extended to earlier investments, this protection was never intended to shield artificial or abusive arrangements.

d) Concept of grandfathering

The Supreme Court clarified that grandfathering protects genuine investments, not layered structures designed solely to exploit treaty benefits.

Vodafone Case: Contextual Foundation, Not a Shield

The Vodafone judgment serves as a jurisprudential starting point rather than a protective shield. Vodafone was decided at a time when neither indirect transfer provisions nor GAAR existed. Judicial restraint in that case was premised on legislative silence.

The Tiger Global ruling operates in a fundamentally altered legal environment. By upholding GAAR’s primacy, the Court clarified that the Vodafone Case does not insulate treaty-based structures from scrutiny once statutory anti-abuse mechanisms are in place. Rather, Tiger Global gives effect to the legislative response that followed Vodafone.

COMPETING ARGUMENTS

The taxpayer’s main arguments

- Treaty protection applied, as the seller was a Mauritius resident holding a valid Tax Residency Certificate (TRC).

- GAAR could not apply because the structure pre-dated 1 April 2017 and was grandfathered.

- A TRC constituted conclusive proof of residence.

- The Authority for Advance Rulings (AAR) erred in rejecting the application at the threshold.

Revenue’s arguments

- Treaty benefits do not override GAAR where abuse is established.

- A TRC is only prima facie evidence and does not bar examination of control, substance, or commercial reality.

- Grandfathering does not protect impermissible arrangements.

- The Mauritius entity lacked meaningful commercial substance.

Supreme Court’s analysis

(a) Investment vs arrangement

A central pillar of the judgment is the Court’s distinction between an “investment” and an “arrangement.”

While Rule 10U(1)(d) of the GAAR Rules grants grandfathering to income arising from the transfer of investments made before April 1, 2017, Rule 10U (2) explicitly removes this protection where the transaction is part of an impermissible arrangement.

The Court held that the mere vintage of an entity or structure does not sanitise it from scrutiny. What matters is why the structure exists and how it operates.

(b) GAAR is not retrospective

While GAAR applies prospectively, the Court clarified that its application to post-2017 income arising from pre-2017 structures does not amount to retrospective taxation. The taxable event is the transfer, not the creation of the structure.

(c) TRC is not conclusive of residency

The Court clearly held that a Tax Residency Certificate does not prevent Indian authorities from examining:

- Control and management

- Commercial substance

- Treaty abuse

(d) AAR was right in rejecting the application

The Supreme Court upheld the Authority for Advance Rulings’ jurisdiction to reject applications at the threshold where a clear prima facie case of tax avoidance exists. Advance ruling mechanisms cannot be used to legitimise abusive arrangements.

Key conclusions of the Court

- GAAR can apply even to pre-2017 structures if they are arrangements rather than genuine investments.

- Treaty benefits can be denied where the arrangement is abusive.

- TRC does not grant immunity from scrutiny.

- Capital gains from indirect transfers may be taxable in India notwithstanding treaty claims.

- AAR rejection was valid and legally sustainable.

Justice J.B. Pardiwala’s concurring observations

Justice Pardiwala emphasised that tax sovereignty is integral to national independence. Treaties must not become instruments for the erosion of the domestic tax base. GAAR, equalisation levy, and source-based taxation reflect India’s modern tax policy aligned with global anti-avoidance standards.

Why similar PE structures exist – but are not treated as abusive.

The judgment clarifies that structural similarity does not equate to tax equivalence. Many multinational groups and private equity funds use intermediary holding jurisdictions. However, permissibility depends on functional reality rather than jurisdictional form.

In contrast, the Tiger Global structure exhibited a disconnect between legal ownership and effective control, rendering the Mauritius entity a passive conduit.

| Factor | Accepted Structures | Tiger Global Structure |

|---|---|---|

| Board authority | Independent | Largely nominal |

| Control & decision-making | Exercised in holding jurisdiction | Exercised from the US |

| Commercial rationale | Fund administration, risk pooling, and regulatory alignment | Primarily treaty access |

| Economic substance | Employees, compliance, fund governance | Minimal operational footprint |

| Role in value creation | Active investment vehicle | Passive conduit |

The Tiger Global ruling does not criminalise treaty use – it penalises treaty misuse.

Final takeaway

The Tiger Global–Flipkart judgment sends a clear message: tax treaties are meant to protect genuine investment, not aggressive tax avoidance. The Supreme Court has articulated a clear principle: tax treaties are instruments to promote cross-border trade and investment, not devices to facilitate tax base erosion.

For foreign investors, substance, governance, and commercial rationale matter more than jurisdictional labels. Structures that lack economic purpose, decision-making autonomy, or risk assumption are vulnerable, regardless of when they were created.

For advisors and policymakers, the judgment provides long-awaited clarity on the interplay between GAAR, treaties, and grandfathering. It aligns Indian jurisprudence with global anti-avoidance standards while preserving space for legitimate tax planning.

In conclusion, the Tiger Global case does not undermine investor confidence it redefines it. Certainty now flows from compliance with the spirit of the law, not from exploiting its technical gaps.

This article is an original explanatory analysis written for educational and professional understanding. It does not reproduce or copy any judgment text or published commentary.